What learning languages and music have in common

Learning French more effectively using principles of musicianship

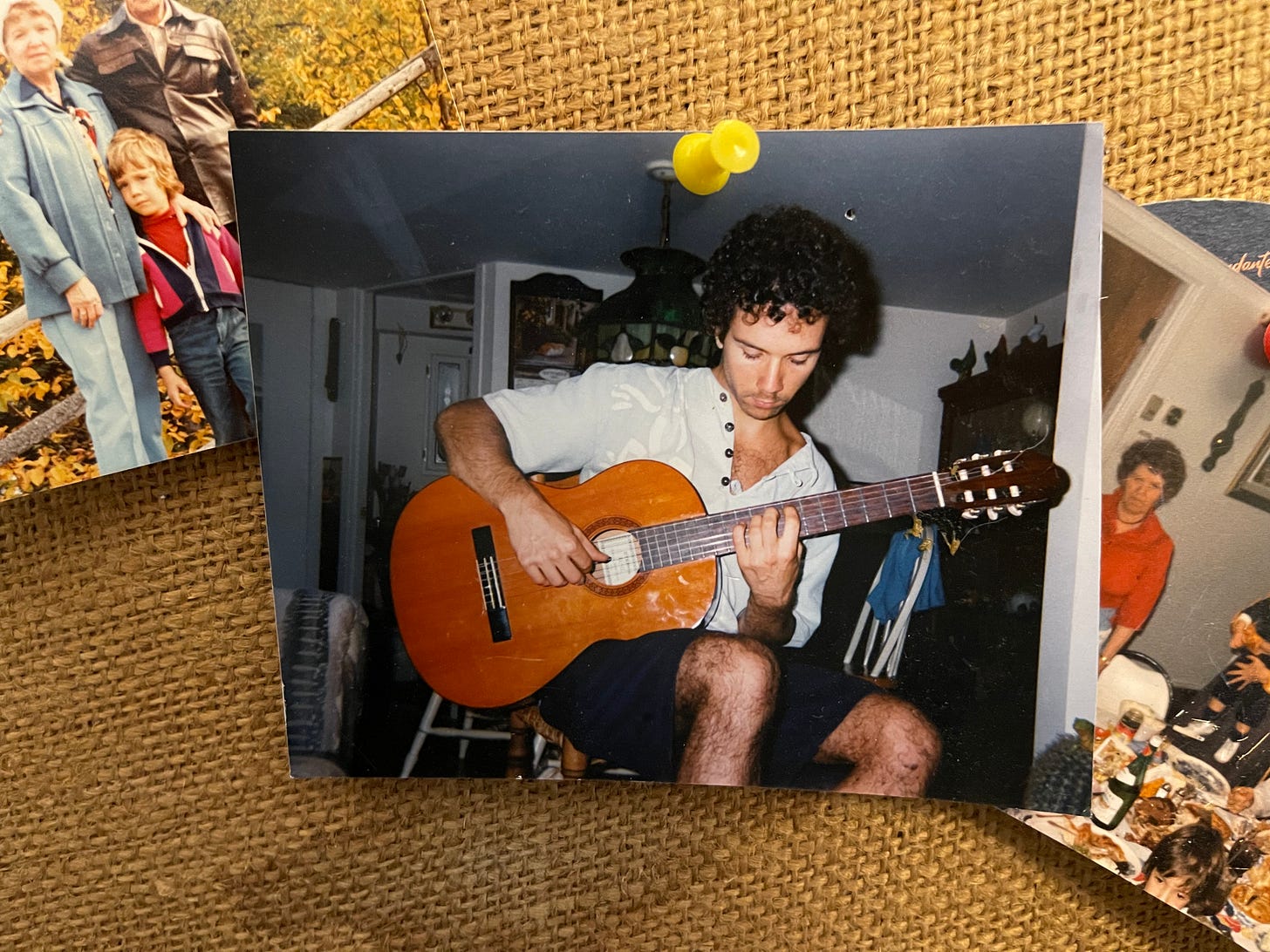

I am a failed musician!

At the late age of 17, nearly 18, I picked up the guitar for the first time.

My friend, nickname was Pedge, saw that I was practicing like crazy, up to six to eight hours a day, but I didn’t have a method. He suggested I attend a music school to learn properly.

I told him, “But I don’t know music theory.”

He answered, “You still hav…